The economic battle against Covid-19 has blurred the boundaries between fiscal and monetary policy. But the threats to central bank independence run deeper than the current crisis.

A spectre is haunting the world of finance: central banks that have lost their power to shock. Charles Goodhart, veteran professor at the London School of Economics, a grandee of international money, has been proclaiming that, when inflation starts to rise again, these traditional guardians of rectitude will no longer be able to raise interest rates.

Over the past 30 to 40 years, central banks were granted widespread statutory independence from political influence in a sweeping worldwide shift. But according to Goodhart’s thesis, they will be forced to bow to government pressure to keep interest rates low and prevent a ruinous spike in the servicing costs of debts massively boosted by the pandemic.

Faced with a stark choice, governments and (it is claimed) increasingly subservient central banks seem to be opting for inflation over default. After all, higher prices inflate away debt – shown historically by booming economies running out of control after wars and plagues. ‘Look back nostalgically at your time of independence,’ Goodhart puckishly tells his central banking audiences. ‘It was nice while it lasted.’

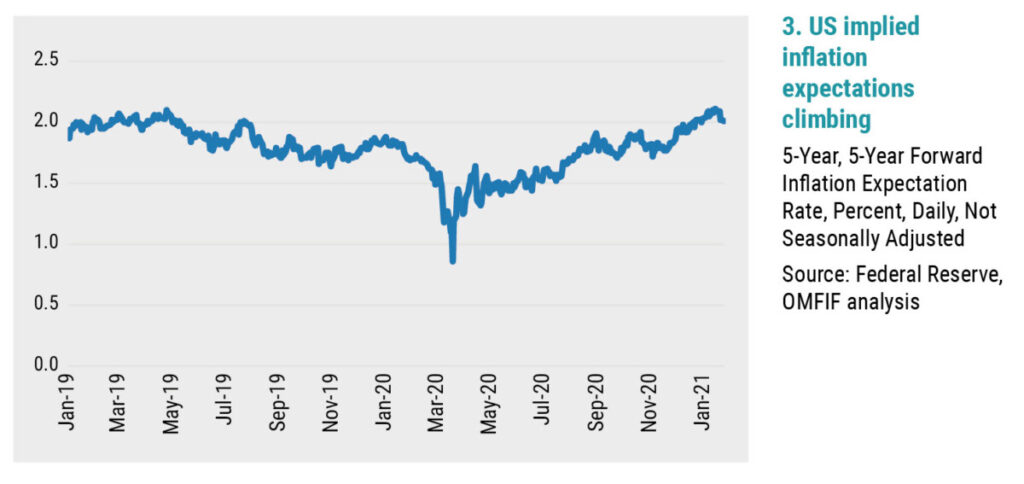

The debate has heated up. Forecasters point to a rise in US inflation beyond the Federal Reserve’s 2% target later this year as the US economy shifts to major post-pandemic expansion after a decade of near-constant undershooting. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen will not wish overtly to undermine Fed independence, but she will try to swing the Fed behind the administration’s pro-growth agenda. Yellen knows her Fed chair successor Jay Powell will not want to upset the government by tightening money when bidding for a second term from February 2022.

There have been frequent squalls over central banks’ waning capacity – perceived and real – to stand up to governments. The battlegrounds include emerging market economies like Turkey, Brazil, Nigeria and Malaysia. Also included is the UK, where the Bank of England is widely regarded as carrying out monetary financing of a gigantic Covid-19 budget deficit – a charge it denies.

However, the independence controversy is most virulent in Europe’s 19-nation economic and monetary union. After more than 20 years, the EMU still resembles an enormous financial and political experiment.

The fulcrum of EMU is Frankfurt, where Germany’s Bundesbank was set up after the second world war with strong legal powers to withstand government pressure, guarding against the excesses of the Weimar Republic and later the Third Reich. Germany’s Weimar hyperinflation in the 1920s was part of a grim chain of money printing episodes ruining currencies and breaking political systems – linking ancient empires to modern emerging markets like Argentina, Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

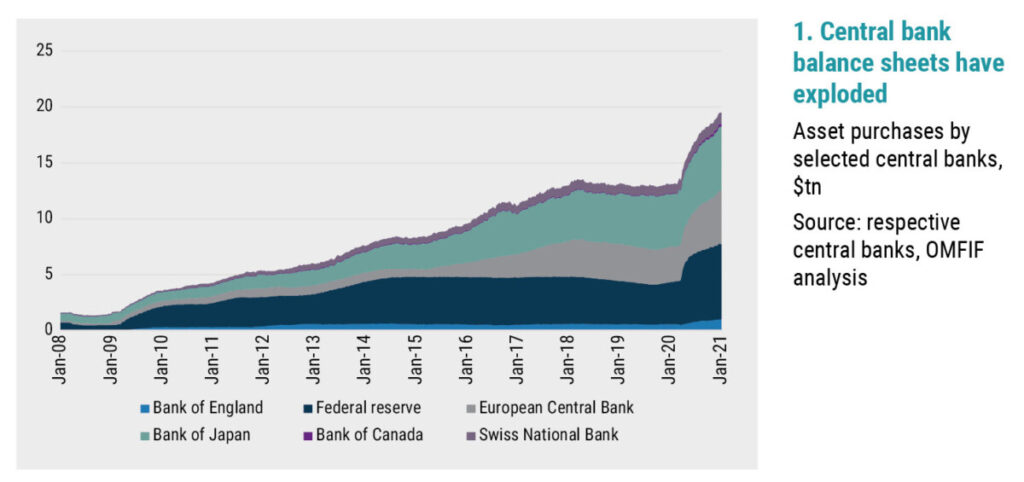

Established in 1998, the European Central Bank was modelled on the Bundesbank, with its independence enshrined in the European treaties. Now, the model appears to be faltering. Conservative Germans voice concerns that enormous central bank government bond purchases before and during the Covid-19 upheavals (Figure 1) are turning these institutions into appendages of finance ministries.

In recent months, including in an OMFIF meeting in November, Jens Weidmann, the Bundesbank president and former adviser to Chancellor Angela Merkel, has spoken of a ‘dangerous dynamic’ of ‘fiscal dominance’. He outlines how central banks risk surrendering independence as they ‘jump to the rescue’, becoming permanent buyers of debt issued by big-spending governments unfettered by market discipline.

To many, in Germany and beyond, such talk is alarmist and exaggerated. François Villeroy de Galhau scotches fears that the ECB is in danger of losing clout. At an OMFIF session in September the silken-tongued Banque de France governor countered traditional German views by suggesting the ECB should more directly widen its mandate beyond targeting purely price stability. The Bundesbank, once a synonym for German monetary hegemony, has lost sway with the birth of the EMU. Weidmann has maintained opposition to some of the ECB’s furthest-reaching credit-easing actions. Yet he has accepted that the Bundesbank generally must give way to a built-in majority on the 25-member ECB governing council favouring a relatively accommodative monetary stance.

Mario Draghi, ECB president in 2011-19, was frequently embroiled in disputes with the Bundesbank chief. Draghi’s successor, Christine Lagarde, a former French finance minister and International Monetary Fund managing director, has taken a far more consensual line to heal rifts between council ‘hawks’ and ‘doves’. But Lagarde has dropped not-so-subtle hints that quantitative easing purchases of government bonds may continue indefinitely.

Mario Draghi, ECB president in 2011-19, was frequently embroiled in disputes with the Bundesbank chief. Draghi’s successor, Christine Lagarde, a former French finance minister and International Monetary Fund managing director, has taken a far more consensual line to heal rifts between council ‘hawks’ and ‘doves’. But Lagarde has dropped not-so-subtle hints that quantitative easing purchases of government bonds may continue indefinitely.

One leading southern European governor on the ECB council fiercely opposes his colleagues calling for a gradual credit tightening as Europe slowly brings the pandemic under control. ‘I am a strong hawk,’ he tells OMFIF, ‘in opposing deflation.’ There were sharp exchanges at the ECB’s meeting on 10 December when it decided to boost emergency bond buying by €500bn and extend it to March 2022. Council members swapped jibes about whether the ECB was taking seriously its mandate to boost inflation to ‘below but close to 2%’ – a level it has undershot for eight years.

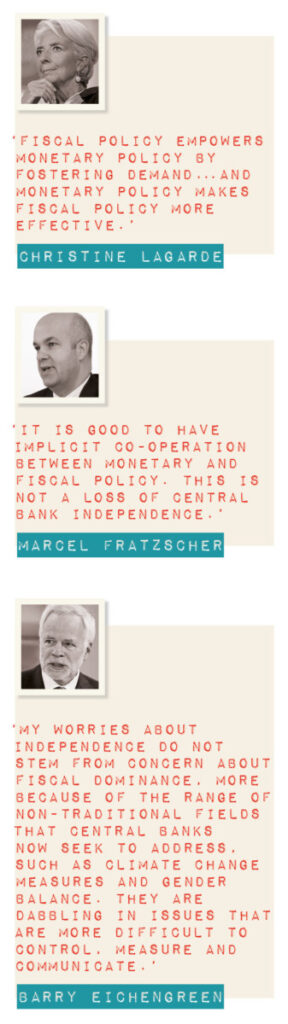

Marcel Fratzscher, a former ECB official who heads the Berlin-based German Institute for Economic Research (DIW) believes the Bundesbank’s narrative on inflation and independence is overdone. Fratzscher echoes a persistent Lagarde theme: the need for coordination between central banks and governments. As Lagarde puts it: ‘Fiscal policy empowers monetary policy by fostering demand … And monetary policy makes fiscal policy more effective.’

Fratzscher tells OMFIF: ‘It is good to have implicit co-operation between monetary and fiscal policy. This is not a loss of central bank independence. Even if central banks were unhappy with fiscal polices, they would be breaching their mandate if they raised interest rates to force governments to change their behaviour. It’s not the job of central banks to discipline governments.’ He adds, ‘If inflation were to rise for a sustained period substantially above the ECB’s mandate, then it would have to act decisively, and I am sure it will.’

Behind the divergences over ‘harmonisation’ lies a deeper question. European governments have still not resolved whether, longer term, the euro area requires a fully-fledged political union to back the ECB’s monetary integration. According to German critics, a transformation towards a system for permanently channelling wealth and income from higher- to lower-performing areas of the EMU may be on the way.

Helmut Schlesinger, former Bundesbank president, at 96 a Methuselah of monetary orthodoxy, tells OMFIF: ‘I am worried there is no real resistance to the ECB’s very large purchases of government bonds, which represent a form of state financing not allowed by the treaty. It seems to me that Chancellor Merkel and her government didn’t recognise the concerns raised in this matter in May by the German constitutional court [when it voiced concerns about illegal monetary financing].’

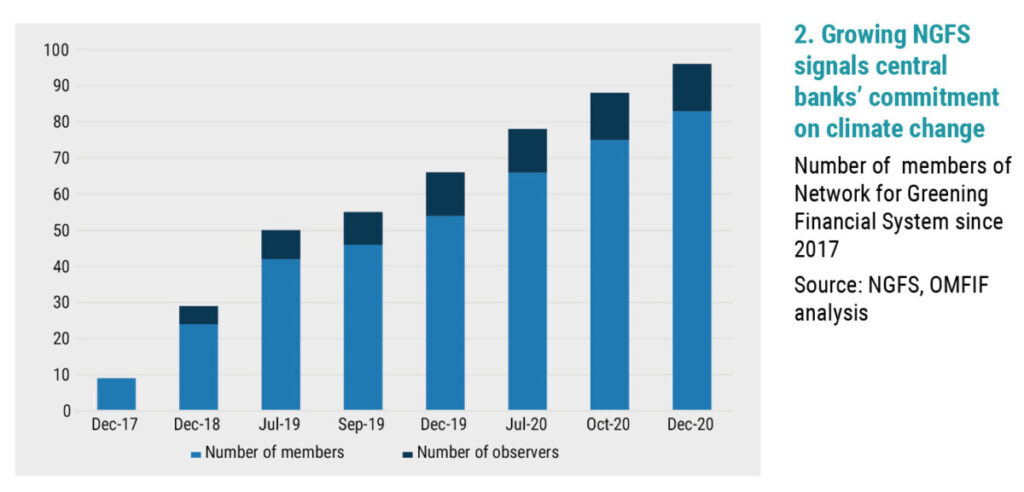

He adds: ‘There seem only two or three members of the ECB governing council who speak out against these policies. The close linkage between fiscal and monetary policies presents a danger for the independence of the ECB. This danger is intensified if the ECB is following too many targets in the political field, for example in measures to alleviate climate change, (Figure 2) which weaken the focus on its primary goal of stability.’

Barry Eichengreen, economics professor at the University of California, agrees with the second part of Schlesinger’s argument. He backs the Lagarde and Fratzscher view that central banks can retain independence under fiscal and monetary policy harmonisation. He adds: ‘My worries about independence stem not from concern about fiscal dominance, more because of the range of non-traditional fields that central banks now seek to address, such as climate change measures and gender balance. They are dabbling in issues that are more difficult to control, measure and communicate.’

Barry Eichengreen, economics professor at the University of California, agrees with the second part of Schlesinger’s argument. He backs the Lagarde and Fratzscher view that central banks can retain independence under fiscal and monetary policy harmonisation. He adds: ‘My worries about independence stem not from concern about fiscal dominance, more because of the range of non-traditional fields that central banks now seek to address, such as climate change measures and gender balance. They are dabbling in issues that are more difficult to control, measure and communicate.’

Underlining the diversity of opinions, Athanasios Orphanides, a former governor of the Central Bank of Cyprus and member of the ECB’s council, complains the ECB has used the broad language of the European treaty to set its own goals, for example in defining ‘price stability’ – and yet has not done enough to produce higher inflation.

He tells OMFIF: ‘Central banks should have the independence to meet their goals but not to set them. The ECB has too much independence and insufficient accountability.’ He claims that the ECB has misused independence by following overly tight Bundesbank-style policies that have raised euro area credit spreads and damaged growth. Now a professor at Boston’s MIT Sloan School of Management, Orphanides – who previously worked at the Fed – stresses the contrast with the US: ‘If the Fed starts making systematic policy errors, Congress can change the law and hold the Fed accountable. The ECB should not be so independent that its policy errors cannot be corrected.’

The ECB’s framework is coming under renewed scrutiny in the bank’s strategy review due to be unveiled in early September. The process gives Weidmann and other governing council hawks unaccustomed influence. Otmar Issing, the ECB’s first board member for economics, oversaw the only other previous review in 2003. He points out how the council’s stringent minority – normally submitting to the majority on operational decisions – will have an effective veto on the outcome of the strategy review, including on the hot topic of climate change, where Weidmann and other orthodoxists oppose interventionism that could expose the ECB to conflicts with its monetary goals. ‘The review should end in unanimous support for the decision,’ Issing tells OMFIF. ‘This will not easily be achieved. Compromises are needed, but the result must deliver a consistent approach.’

The ECB’s framework is coming under renewed scrutiny in the bank’s strategy review due to be unveiled in early September. The process gives Weidmann and other governing council hawks unaccustomed influence. Otmar Issing, the ECB’s first board member for economics, oversaw the only other previous review in 2003. He points out how the council’s stringent minority – normally submitting to the majority on operational decisions – will have an effective veto on the outcome of the strategy review, including on the hot topic of climate change, where Weidmann and other orthodoxists oppose interventionism that could expose the ECB to conflicts with its monetary goals. ‘The review should end in unanimous support for the decision,’ Issing tells OMFIF. ‘This will not easily be achieved. Compromises are needed, but the result must deliver a consistent approach.’

The review is expected to result in ‘not too much change’ in its inflation framework, Issing says. The 2003 review upheld the ECB’s 1998 definition of price stability as an inflation rate of below 2% over the medium term, but added the refinement of ‘close to’ to safeguard against deflation. He believes the ECB will not signal it is going soft on inflation. ‘This time I believe the ECB might simply settle on a figure of 2%. The question is: Will the ECB see this goal as symmetric, i.e. will it deal with both overshooting and undershooting in similar fashion.’

The fundamental problem facing central banks has been recognised for years: they are operating in too many fields. As veterans like Schlesinger and Issing emphasise, the widening of central banks’ sphere of action since the 2008 Lehman Brothers bankruptcy into areas like banking supervision, as well as large-scale QE, has limited their room for manoeuvre. A 2012 OMFIF-EY report, ‘Challenges for central banks: wider powers, greater constraints’, underlined far-reaching questions about their operational freedom.

The LSE’s Goodhart sees the threats growing mainly outside Europe. ‘The central banks in Japan and India have lost their independence, Latin America never had it, the US is on the verge of losing it. The independence of the ECB is protected by treaty – but I’m more worried about Jay Powell.’ Faced with Yellen in the Treasury, Goodhart says fiscal dominance seems on the way in the US. ‘I think he will do whatever she likes.’

As for inflation, Goodhart thinks it’s on the way back – a view gaining ground because of the Biden recovery plan, signalled by rising longer-term US interest rates (Figure 3).

‘Once vaccination has overcome the Covid-19 pandemic, say by summer 2021, a surge in consumer expenditure and demand could lead to a blip in inflation. If that does not exceed 5%, central banks will probably welcome the counterbalance to the previous undershoot, claiming it is purely temporary.’

‘Once vaccination has overcome the Covid-19 pandemic, say by summer 2021, a surge in consumer expenditure and demand could lead to a blip in inflation. If that does not exceed 5%, central banks will probably welcome the counterbalance to the previous undershoot, claiming it is purely temporary.’

More likely, Goodhart believes, is that inflation will remain significantly higher than targeted in 2022-23. This will lead to different scenarios including conflict with politicians, most of them with unpleasant outcomes. ‘Ultimately the political authorities have the whip hand, whether in authoritarian or democratic countries. Central banks must be aware where their limits lie.’

David Marsh is Chairman at OMFIF.

Enter your details to download the rest of the Bulletin: The threats to central bank independence