Britain’s forced departure from the exchange rate mechanism of the European Monetary System 30 years ago was a landmark in UK and European economic history. The saga of monetary misfortune that culminated on 16 September 1992 contains significant lessons for contemporary policy-makers.

The upset reinforced Euroscepticism towards the European Community (later Union) within the UK Conservatives, Britain’s dominant post-war party of government. This triggered a train of events, including the 2016 referendum that ultimately brought departure from the EU in January 2020.

Yet ‘Black Wednesday’ also ushered in a successful Bank of England-Treasury inflation-quelling regime and a period of economic stability not punctured until the 2007-08 financial crisis. The OMFIF Press published a book on the upheavals and the aftermath – Six Days in September: Black Wednesday, Brexit and the Making of Europe – to mark the 25th anniversary of the crisis in September 2017, available for £9.99 on the OMFIF website.

The reverberations extend to today’s fluctuating politics. Queen Elizabeth’s death and King Charles’ accession after his mother’s 70-year reign come at a time when Britain has had four (Conservative) prime ministers and six chancellors in six years since 2016 – the most volatile period since the 1920s. There are echoes with current oscillating financial markets. The ERM laid the groundwork for economic and monetary union in Europe, implemented in 1999. But the strains 30 years ago illustrated the perils of EMU ‘fragmentation’ which – despite near-continuous crisis-fighting since 2010 – have still not been banished.

A month after the 1992 upset, Helmut Schlesinger, president of the German Bundesbank, whose injudicious (though partly justified) remarks in a newspaper interview on 15 September provoked sterling’s collapse, met Elizabeth on an official visit to Germany. She asked him ‘whether speculators could really be so strong?’ Schlesinger replied, ‘Yes madam, in a system of fixed exchange rates with high differentials in the rate of inflation, they can.’ Schlesinger, who turned 98 on 4 September, is no longer active in public life. Behind the scenes he has been playing a discreet subsidiary role stiffening the sinews of today’s Bundesbank against negative interest rates (now abandoned) at the European Central Bank.

Prime Minister Liz Truss, in office for just 10 days, faces extensive challenges with loyal, largely untried ministers. Given the size of the UK’s budget and current account deficits and uncertainties over Truss’s economic and energy policies, there is a risk of major pressure on sterling that could disrupt her government. Here are six lessons from 30 years ago that she and other policy-makers should be heeding:

1. Maintain cohesion between the government and central bank

Britain’s membership of the ERM – which it joined on 8 October 1990 at the wrong time, for the wrong reasons and at the wrong exchange rate – provides a case study in faulty understanding between the Bank of England and Treasury. The deal was hatched in great secrecy and without any discussion in cabinet. The Bank of England, under Governor Robin Leigh-Pemberton and his deputy (and successor) Eddie George, strongly opposed cutting interest rates at the same time as joining. George from the outset took a more sceptical line on ERM membership than Leigh-Pemberton. These strategic warnings, made in private, undermined sterling when pressure on the exchange rate erupted in 1992.

Present-day discord, by contrast, has been expressed in full public view. Truss, formerly foreign secretary and trade secretary in Boris Johnson’s government, has voiced frequent though largely unspecified complaints about the Bank of England’s failure to control inflation. She will now have to strike a delicate balance. Ordaining changes in the Bank’s operating framework and personnel policies may be legitimate and necessary. But undermining the independence of the Bank’s monetary policy committee under Andrew Bailey, the heavily criticised governor, could hit sterling and raise government borrowing costs, lowering not improving Britain’s economic performance.

2. Signal institutional continuity to foreign partners

One factor behind sterling’s disarray in 1992 was a breakdown in communications between the Bank of England and Bundesbank. Leigh-Pemberton and Schlesinger, a Bundesbank veteran who took the top job only in 1991 when Karl Otto Pöhl resigned, had no time to work out a personal understanding.

Similar constraints applied to Mervyn King and Otmar Issing, the two central banks’ chief economists. The two men (who 30 years later have become firm friends) met for the first time two days before Black Wednesday, when King flew to Germany (accompanied by the Treasury’s Alan Budd) on a fruitless mission to persuade the Germans that sterling was fairly valued. King carried out his task with dogged persistence. Even if he and Issing had known each other better, the UK mission – in view of Britain’s loss of competitiveness within the ERM – would have been doomed to failure.

With sterling floating and Britain outside the EU, 2022’s institutional arrangements are not comparable. Yet Britain’s unsteady EU relationships and need to finance a large current account deficit necessitate sound intergovernmental links. Truss’s abrupt and unceremonious sacking of Tom Scholar, the long-serving Treasury permanent secretary, on the first day of her administration has been heavily criticised by experienced UK government officials. It has also raised eyebrows among policy veterans abroad. Truss has emphasised Thatcherite credentials, but her 1980s predecessor was far less heavy-handed – and also gave fiscal repair priority over tax cuts. Margaret Thatcher had ideological differences with Douglas Wass, the Treasury’s Keynesian permanent secretary when she took power in 1979. But he helped her over the 1981 budget and stepped down (replaced by Peter Middleton, more open to Thatcher’s monetarist leanings) only when he reached the then retirement age of 60 in 1983.

3. Avoid airing destabilising policy discrepancies

Differences within government dogged increasingly desperate efforts to keep sterling within its 1992 ERM bands. Divergence was particularly marked between John Major, Thatcher’s successor as prime minister, who masterminded ERM entry as Thatcher’s chancellor of the exchequer, and Norman Lamont, who became chancellor when Major took over. Lamont, who was not involved in joining the ERM and tried unsuccessfully to push Major towards suspending membership in August 1992, ended up in the spotlight of sterling’s ignominious exit. Withdrawal made a nonsense of Major’s claim, just six days before 16 September that Britain would never take ‘the devaluers’ option’. The Conservative party’s perceived loss of economic competence helped spur Major’s heavy defeat against Tony Blair’s revitalised Labour party in the 1997 election.

The dilemma for Truss is unlikely to be as spectacular. However, policy discrepancies are likely to emerge as early as 22 September, when the MPC announces its next interest rate decisions, after a meeting postponed by Elizabeth’s funeral. Truss and her supporters see the government’s £150bn energy support plan – full details of which are still being worked out at a Treasury unsettled by Scholar’s dismissal – as bringing down headline inflation. This would reduce the MPC’s need to tighten money further. Many on the committee, by contrast, will see additional government borrowing and spending as inflationary, raising the necessity of further interest rate rises. The divergence will be an early test for Truss as she battles not only the Labour opposition but also disaffected Conservative MPs. Truss has gone to great pains to eliminate this faction from her government, but at the price of deepening divisions, distrust and potential disloyalty of her backbenchers.

4. Don’t make promises you can’t keep

One of the most piquant moments of sterling’s ERM misadventures was when Lamont, on 26 August 1992, announced Britain would do ‘whatever is necessary’ to maintain sterling’s position in the ERM. This foreshadowed the celebrated statement 20 years later by Mario Draghi, who said on 26 July 2012 the ECB would do ‘whatever it takes’ to preserve the euro. The difference was that Draghi had been assured of full support for ECB initiatives from Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, whereas Lamont did not have sufficient firepower from the Treasury, Bank or European institutions (especially the Bundesbank) to back his position.

Truss, a former Liberal Democrat who voted in the 2016 referendum to keep Britain in the EU, over her political career has shown frequent adaptability in her policy approaches. Only six weeks ago she said she opposed ‘hand-outs’ to curb the cost-of-living crisis – a statement that stands in diametric opposition to the £150bn energy price cap scheme. Ensuring reasonable consistency in policy pledges will be a major task.

5. Allocate responsibility for losses on the central bank balance sheet

The ERM debacle led to several attempts to measure the loss to the exchequer of enormous, unsuccessful Bank of England intervention to shore up sterling. The British government ended 16 September with negative foreign exchange reserves. In December 1993, the Treasury – with considerable caveats over calculation – gave a figure of £3.3bn for the accounting loss.

Disputes over apportioning institutional risk for foreign exchange intervention added to European acrimony. In the 1993 currency turbulence that followed the 1992 crisis, the Bundesbank refused intervention on its own account to support the French franc, insisting the Banque de France should bear the risks of borrowing D-Marks to sell for francs (a policy on which France eventually made a profit). In summer 1992, the Italian government in Rome decided against a ‘jumbo’ foreign loan to support the lira because of the foreign exchange risk. The UK Treasury by contrast contracted a Ecu10bn loan, failing to realise that George Soros, the New York speculator, was simultaneously amassing $10bn to match against sterling – a bet, just a few days later, he would resoundingly (and profitably) win.

Today’s problems stem largely from accounting losses on the Bank of England’s £895bn of domestic assets acquired under quantitative easing through UK government bond purchases, much of it under Bailey. In view of sharp falls in bond prices, mark-to-market losses have been estimated at above £100bn.

Pressure is rising for the government to give full details on the Treasury indemnity to the Bank over the QE purchases. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research has calculated that the UK Treasury has lost taxpayers £11bn by not taking out insurance against rising interest rates. The issue has been highlighted by John Redwood, a senior backbench MP, Truss supporter and critic of undue current Bank tightening.

These difficulties run parallel to a behind-the-scenes debate at the ECB and national central banks (the ECB’s shareholders) over very large accounting losses on the ECB’s stock of QE bonds amassed since 2015. The Bundesbank has been highlighting the Eurosystem’s need to take into account mark-to-market losses. The ECB has been conducting stress tests on NCB balance sheets’ resilience in the light of bond market reversals. All this is germane to the discussion over ‘risk-sharing’ on the ECB’s new transmission protection instrument. The ECB is keeping silent on the details partly to maintain some disciplinary pressure on a new Italian government and partly because it fears the consequences of full transparency.

6. Maintain high foreign exchange reserves

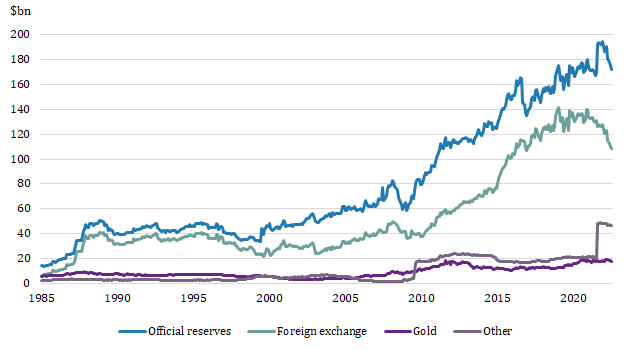

The shadow of Black Wednesday lies behind the UK’s higher-than-average reserves accumulation over 30 years (Figure 1). In 2010 – nearly 20 years after the UK ran out of reserves on 16 September – the UK government, through George Osborne, chancellor of the exchequer under Prime Minister David Cameron, decided to increase international reserves through sustained foreign borrowing.

Figure 1. UK’s reserves accumulation higher than average since 2010

Figures are end-year

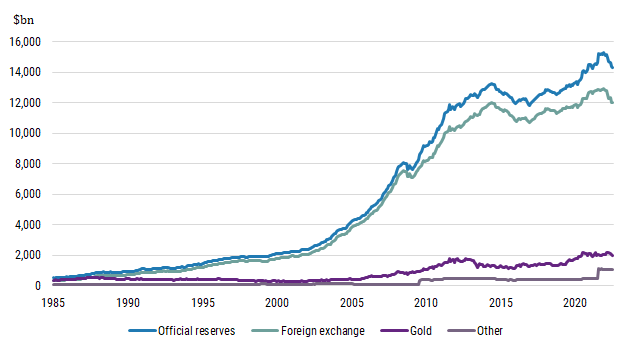

Figure 2. Global reserves accumulation

Figure 2. Global reserves accumulation

Source: IMF International Financial Statistics via Refinitiv

Source: IMF International Financial Statistics via Refinitiv

Total foreign reserves – including foreign exchange, gold, special drawing rights and the UK’s reserve position at the International Monetary Fund – have recently been fluctuating between $180bn and $200bn. Foreign exchange reserves at end-2021 were 159% and 288% higher than in 2010 and 1990 respectively, while total reserves were up 98% on 2010 and 373% on 1990 – although the reserves have fallen sharply in recent months, apparently mainly reflecting valuation changes caused by the rising dollar and falling prices of bonds and gold.

The precise reasoning behind the decades-long rise remains opaque: the exchange rate regime has not changed since Britain left the ERM, and the UK has not engaged in foreign exchange intervention since 1992. In a statement that seems still to encapsulate policy today, Osborne in 2010 underlined the need for a further rise in reserves (since carried out) and cited three reasons: ‘The global economy is still uncertain, the UK’s reserves are relatively small compared to many other advanced economies, and the UK still needs to remain resilient to possible future shocks.’

Analysing possible shocks ahead, Jagjit Chadha, NIESR director, has this advice for the Truss government: ‘Set feasible, orthodox policy plans that are subject to expert scrutiny. This goes for Turkey and Sri Lanka now and for any plans under Trussonomics for unfunded tax cuts, huge increases in public expenditure and undermining of our economic institutions – Bank of England, Office for Budget Responsibility and the Treasury.’ Expounding on the exact reasons for substantial official currency holdings will hardly be a priority. However, the government would be well advised to maintain reserves at a high level – a hedge against the substantial risks it faces in nearly all areas of economic policy.

David Marsh is Chairman, OMFIF.