Italy and France look set to top Germany’s European policy agenda if, as expected, Finance Minister Olaf Scholz heads a new Berlin government taking office before Christmas.

There were few hints of concrete European initiatives in the three-party document published on 15 October as a prelude to formal coalition talks between Scholz’s Social Democratic Party (SPD), Greens and liberal Free Democrats (FDP). However, Scholz seems likely to bank heavily on reaping European goodwill. He will seek benefits from Germany’s one-year presidency of the G7 industrialised countries and France’s six-month stewardship of the European Union, both starting on 1 January.

The potential coalition partners in what would be Germany’s first federal-level ‘traffic light’ partnership – named after the trio’s individual colours – have in the past fortnight shown almost excessive politeness. But they will face strains as wrangles surface on staking claims for the finance ministry post, where perpetually well-groomed FDP leader Christian Linder so far has put in the stronger bid over rival Robert Habeck, the Greens’ more dishevelled-looking co-chair.

The 4,500-word preliminary document was long on aspiration and high-blown phraseology, yet skirted round detail, especially on financing ambitious climate mitigation, infrastructure and social plans. Many of these issues, reflecting deep differences particularly with the FDP on the virtues of a state- and deficit-led investment drive, are likely to resurface when formal coalition talks get under way.

In a surprising embrace of financial engineering concepts, Green co-Chair Annalena Baerbock has spoken of devising corporate vehicles to provide off-balance sheet funding for environment-friendly investments.

Those close to Scholz believe that, provided he clinches the chancellorship, Germany’s putative leader will quickly pursue a charm offensive with Rome. Berlin will need to build further on ideas earlier in Scholz’s finance ministry to reinforce banking union with a deposit insurance scheme for European banks as well as reforms of the currently in-abeyance stability and growth pact.

Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, anxious to consolidate his so far successful eight-month premiership, will demand action as well as warm words from Berlin. The defeated Christian Democratic Union and its Bavarian Christian Social Union allies, likely to go into opposition, will be much more hostile to suspected German concessions on Europe than when in government under Angela Merkel, now caretaker chancellor.

Scholz wishes to secure an SPD-Greens-FDP coalition as speedily as possible to lend energy to what he hopes will be a reforming chancellorship. And he wishes to deprive the FDP of any chance to reopen partnership talks with a re-established CDU/CSU after the conservative parties replace Armin Laschet, their ill-fated candidate in the 26 September poll.

Scholz’s Italian connection stems partly from a campaign to rebuild bridges with the European Central Bank. Soon after becoming finance minister in March 2018 under the SPD’s coalition agreement with Merkel, Scholz developed a good personal rapport with Draghi, then ECB president.

Scholz helped smooth the way to a debt exit plan for Greece after eight years of international bail-outs. This secured a return to normal Greek financing, alleviated the ECB’s role in policing Greek debt and healed some fractures between Draghi and Germany during Wolfgang Schäuble’s eight years as finance minister.

In a drawn-out section on Europe, the 15 October preliminary three-party accord tilts strongly towards Emmanuel Macron by setting an aim of buttressing Europe’s ‘strategic sovereignty’ – a favourite slogan of the French president. All three putative allies issued robust statements of European support in election manifestos. But the combined SPD-Greens-FDP stop short of ground-breaking initiatives. Typical of the effort to skate over potential differences was the statement in the preliminary accord favouring ‘stronger co-operation between national European armies.’ This falls well below a clarion call for a European army that has been high up among federal European blueprints for 70 years.

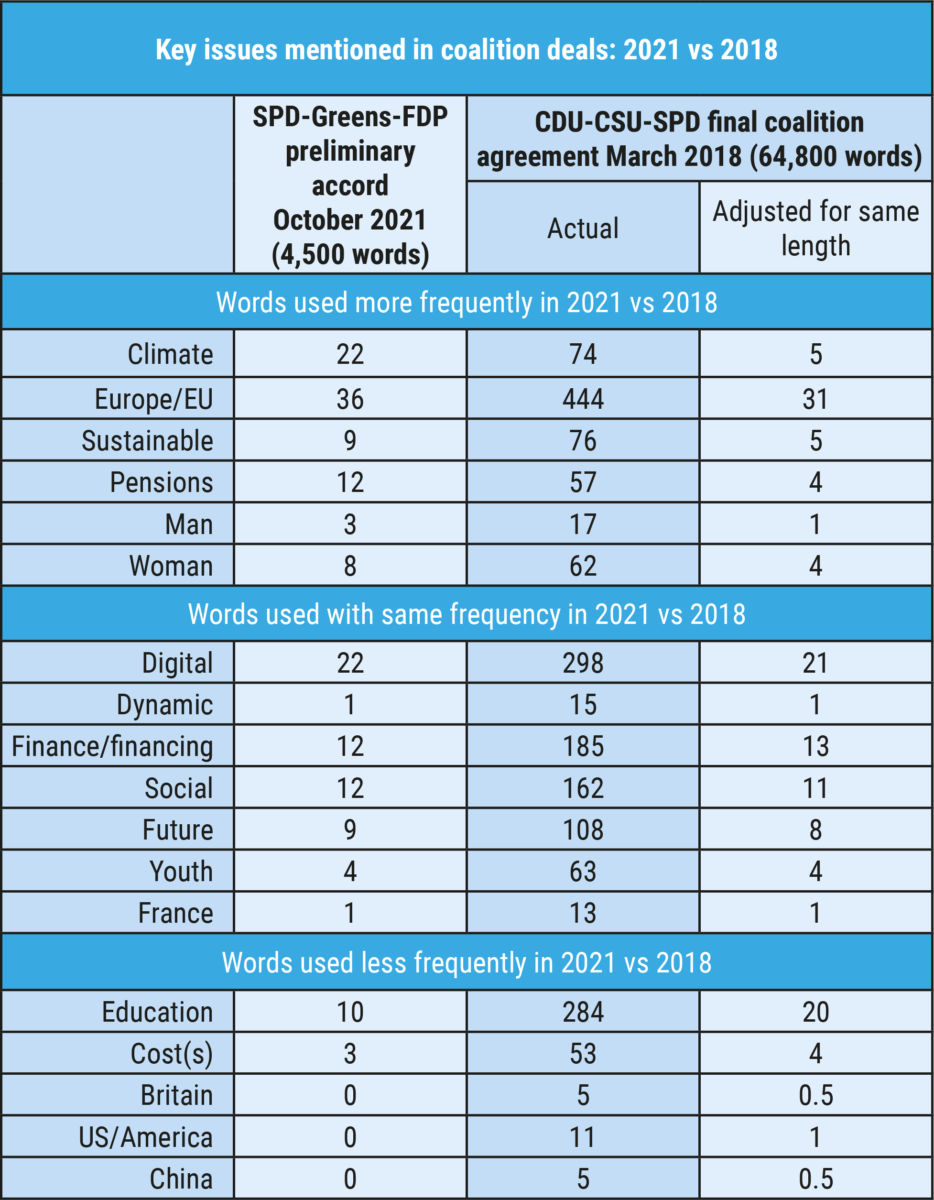

Figure 1: Buzzwords in German political agreements

Comparisons between the preliminary ‘traffic-light’ document and the detailed final coalition agreement in March 2018 between the CDU, CSU and SPD are distorted by the widely differing lengths of the two documents (see table). The lengthy gestation of Germany’s last coalition, which followed the much-documented 2017 breakdown of talks between the CDU/CSU, Greens and FDP, has served as a warning to all parties in the latest coalition bargaining.

The 2021 Greens’ advent is underlined by the greater prominence of words like ‘climate’, ‘sustainability and ‘woman’. Much-used buzzwords in German political parlance are ‘digital’ and ‘digitalisation’, expressing general desire to move the country forward in a field where many critics at home and abroad point to its grave shortcoming. ‘Digital’ is used with roughly equal frequency in the two texts (adjusting for the much shorter length of the 2021 statement).

However, all partners are aware that modernising Germany’s economic structures will require efforts that go much further than crafting phrases in coalition documents.

David Marsh is Chairman of OMFIF.

On Friday 22 October, OMFIF is bringing together experts from the Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs, Federal Ministry of Finance and the Institut der Deutschen Wirtschaft in an off-the-record roundtable to discuss Germany’s changing political and economic landscape. Request to attend here.