Germany and the European Central Bank are close to resolving the impasse over a threatened constitutional court ban on Bundesbank participation in ECB quantitative easing. A lifting of legal uncertainty over ECB government bond purchases, accompanied by a big boost in German fiscal activism, forms part of markedly improved European policy coordination spurred by the coronavirus crisis.

Last month’s Karlsruhe court verdict requesting an ECB ‘proportionality assessment’ on costs and benefits of €2.2tn in public sector bond purchases has represented a pyrrhic victory for 1750 German litigants after a five-year lawsuit.

Jens Weidmann, the Bundesbank president, in coming weeks looks set to play an ambassadorial role providing the German government and parliament with copious ECB analysis of its QE programmes. An elaborately balanced compromise will pave the way for subsequent Karlsruhe approval, maintaining the ECB’s vaunted political independence and avoiding a potentially fatal schism at the heart of the euro bloc.

Weidmann’s 17 June video link appearance at a closed hearing of the Bundestag European Union committee will mark a milestone in a three-month Karlsruhe timetable for the German government and parliament to ensure the ECB reviews the ‘proportionality’ of its policies. Weidmann will follow a line set down by Christine Lagarde, the ECB president, at a meeting of the European parliament economic and monetary affairs committee on 8 June.

She stressed the prospect of a ‘good solution’ to the court wrangle and underlined how ‘the ECB continually monitors the proportionality of its instruments’. Questioned by European parliamentarians over resolving the dispute, she held out the prospect of support for ECB governing council members (without naming Weidmann) who might help to broker a deal.

‘This is so political,’ said one leading committee member afterwards. ‘She [Lagarde] is obsessed by her independence. But if she and the ECB’s legal advisers believe this interaction with the parliament is useful to her, then she will quote it and use it [in the proportionality review].’ A key element of the ECB’s thinking appears to use its official ‘account’ of its monetary policy meeting on 4 June as part of the proportionality statement for the German parliament and then indirectly to the court. The ‘account’ – a governing council-sanctioned document summarising the discussions and reasoning behind decisions at policy meetings – will be released on 25 June covering the meeting last week that decided a €600bn increase in the ECB’s emergency pandemic bond-purchase programme. Demonstration that the council discussed positive and negative consequences of bond buying, as well as mechanisms for eventually ending its various QE programmes (both the PSPP and PEPP), will help fulfil Karlsruhe’s legal requirements.

The legal and political manoeuvring over the ECB coincides with last week’s further proposed €130bn German fiscal expansion and the European Commission’s €750bn recovery plan, both underlining new Berlin budgetary activism.

Isabel Schnabel, the German representative on the ECB’s six-person executive board, said on 10 June that European fiscal and monetary policy were now acting ‘in a complementary way’. However, it would be a mistake for the ECB to scale back monetary measures. ‘Fiscal action has an impact by acting on the outlook. But it is not a substitute [for monetary policy].’

With the European Union recovery fund still under political discussion and requiring unanimous approval across 27 member states, questions remain over its implementation. Even after compromise is reached, there are doubts as to whether payments will be disbursed quickly enough to meet the pandemic’s impact.

Regarding the planned €500bn grant element of the proposed fund, the vast majority of commitments are scheduled to be agreed in 2020-22. However, only around an estimated €100bn will be spent within that time of greatest required support.

This is chiefly because of practical and technical requirements of project design and approval, particularly for promoting a more digital and low-carbon economy. Countries most in need – such as Italy – may not have the technical expertise and resource capacity to implement project straight away.

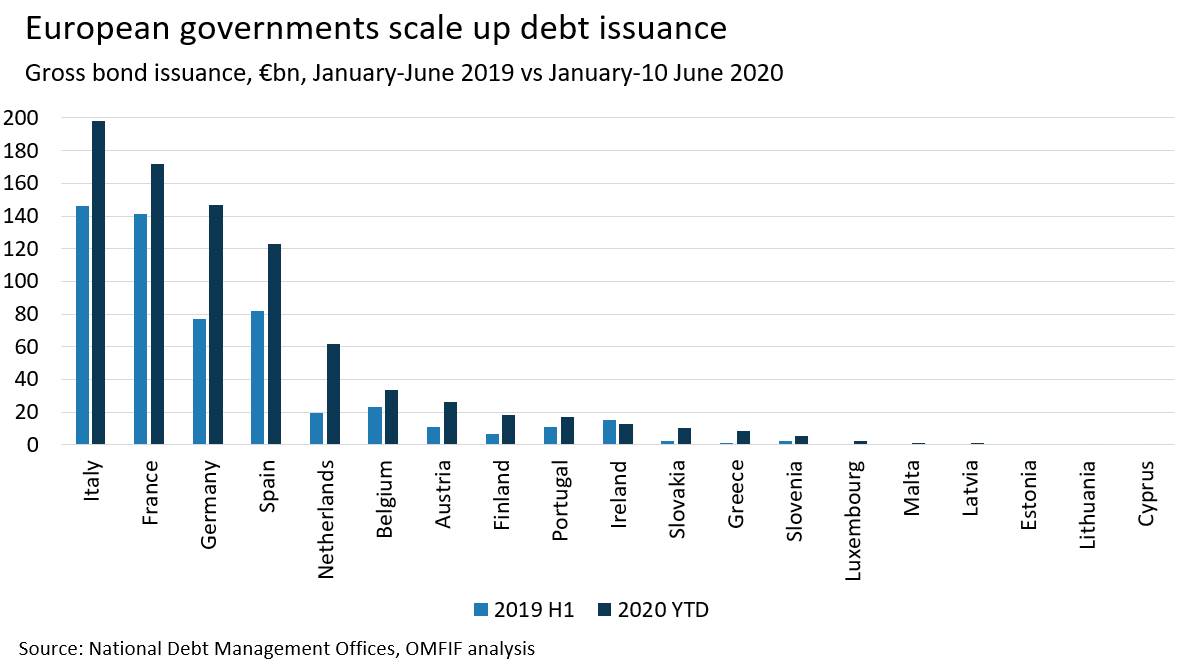

The recovery instrument will be financed by new EU debt issuance, taking place in parallel with disbursed payments. Combined with other EU support programmes, the recovery fund will need to be coordinated with the ECB’s PEPP, designed to be ‘temporary’ while the pandemic crisis lasts. Niels Thygesen, the Danish chairman of the EU’s fiscal board, told a virtual OMFIF meeting on 10 June that the ECB could ‘hold the fort’ with its bond purchases for the second half of 2020, but ‘it can’t go on forever’.

At the current pace of PEPP purchases (around €30bn per week) the enlarged €1.35tn envelope would be exhausted by February 2021. Depending on how the pandemic evolves, the ECB could reassess its strategy and reduce the monthly pace to extend the programme through to a longer horizon. Alternatively, it could extend the PEPP further, by the end of this year. The Bundesbank is aware that this could trigger more lawsuits.

The PEPP gives the ECB flexibility in regional distribution of bond purchases. This is unlike the PSPP which – in theory – is bound by the capital key governing the size of members states’ economies rather than their debt. Since PEPP purchases began in March, Italy has been the biggest beneficiary with a €8bn positive deviation from the capital key. Spain, Germany, Greece and the Netherlands also have small-scale positive deviations. At the other end of the spectrum, France has registered a €12bn negative deviation.

The ECB’s decision on 4 June to introduce reinvestments to the PEPP programme is critically important, as it enables the central bank to correct deviations from the capital key over a longer-term horizon. For the PSPP, in effect since 2015, cumulative deviations from the capital key have resulted in over-purchases for Italy and Spain (respectively at €17bn and €10bn) and under-purchases for Germany and the Netherlands (respectively €31bn and €13bn), as documented in OMFIF’s Central Bank Policy Tracker.

David Marsh is Chairman and Danae Kyriakopoulou Director of Research and Chief Economist of OMFIF.