Major advanced economies and China face daunting fiscal dynamics. Given slow potential growth and difficult demographic prospects, managing economies will only get tougher over the next decade. Populism will continue rising. There is no easy solution.

It’s an ugly picture

Liz Truss, the UK’s most short-lived prime minister, challenged bond vigilantes. They struck back with vengeance. Chancellor Rachel Reeves seeks to abide by UK fiscal rules. But with limited growth, the UK is hard-pressed to find budgetary resources to sustain the social safety net while promoting stabilisation.

In France, President Emmanuel Macron cycles through prime ministers amid low growth while trying to introduce longer-term reforms and grapple with bleak fiscal dynamics. Italy keeps its deficits in check, but the hefty debt stock leaves scant space. China’s debt appears relatively low, but deficits are climbing, opaque data don’t account for massive contingent liabilities and the growth trajectory is downhill.

In the US, Democrats and Republicans devote lip service to fiscal responsibility as debt and deficits pile up. They ignore reality or tout American exceptionalism – a smokescreen for a lack of intestinal fortitude to raise revenue, slow entitlement spending and deal with inexorably rising interest expense.

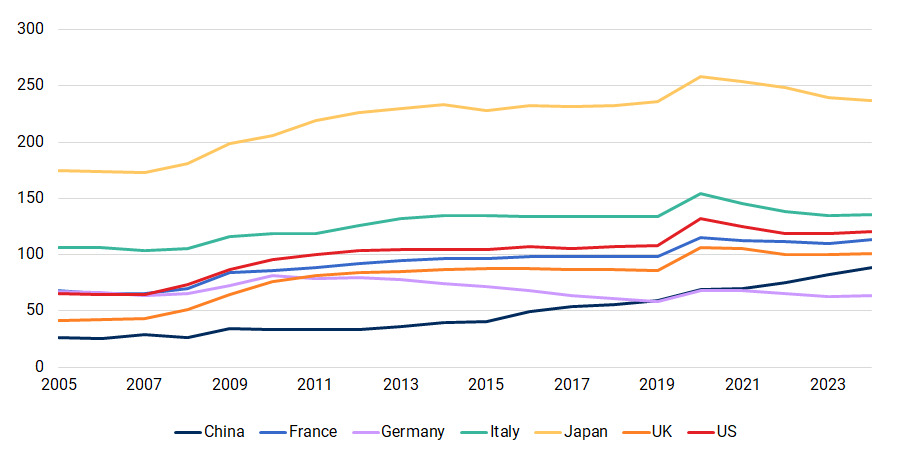

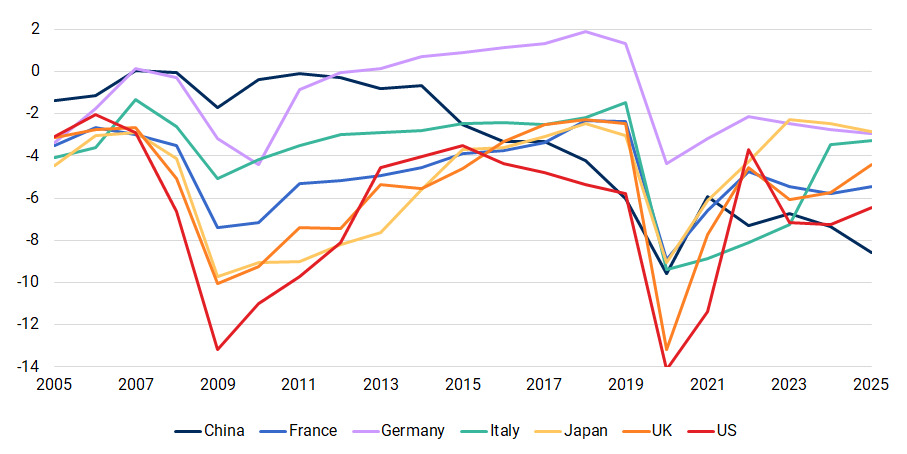

The common denominator: debt stocks are already high, deficits continue and interest bills are rising; growth is anaemic; fiscal space is constrained, let alone when another shock comes; and increased issuance undergirds upward pressure on yield curves.

There is no silver bullet

Policy-makers are blithely averting their eyes from what awaits. Possible outcomes appear implausible or bad.

Surging growth to the rescue? Don’t count on it. The outlook for potential growth is anaemic. China’s is slowing on the back of demographics and an unsustainably high and rising incremental capital output ratio. The US outperforms Europe, but potential growth of 2% will hardly let America grow its way out. The Donald Trump administration’s snake oil is to claim the ‘big beautiful bill’ will push potential growth up to 3%.

If that argument fails, talk about the wonders of artificial intelligence. Perhaps AI will boost potential growth, but large adjustment costs could be associated with AI displacements and technological changes only slowly diffuse into daily economic life.

In Europe, the elixir is constant ramblings about perfecting the single market or implementing the recommendations from the Mario Draghi report – the latest installment in Europe’s never-ending quest for countries to implement structural reforms that societies eschew.

Figure 1. General government gross debt to GDP ratios

Source: International Monetary Fund World Economic Outlook, April 2025

Do the responsible thing? Ha-ha. Political leaders are paid to lead, a risible thought these days. Instead, they squabble and paint simplistic and polarising pictures. They fear that raising revenue will hurt activity or upper-income constituencies, while behind practically every expenditure lies an untouchable vested interest.

In 1990, President George H.W. Bush convened Democratic and Republican leaders, resulting in a budget summit agreement that cut spending and raised taxes. The idea of such a summit being feasible today seems like pie in the sky. The situation appears little different elsewhere.

Bye-bye central bank independence. Advanced economy central banks are mandated to deliver price stability (in the US’s case price stability and maximum employment). But fiscal pressures could lay siege to independence. If fiscal largesse places unsustainable pressures on medium- and long-term rates, or markets go on strike and resist being force-fed new Treasury paper, central banks could find themselves under the gun to absolve governments of their responsibilities. Yield curve control or quantitative easing could follow, with central banks doing so under the guise of financial stability – not monetary policy – concerns.

Such fiscal dominance and financial repression would compel central banks to deliver cheap government finance. Many argue that President Donald Trump’s call for a 1% Fed Funds rate and saving the government money is a harbinger. Others observe that if the Bank of Japan can hold half of the Japanese government bond market and inflation stays tame, why can’t others do so?

Figure 2. General government deficit to gross domestic product

Source: IMF WEO, April 2025

Inflation. Sustained moderately higher inflation could quickly reduce debt-to-gross domestic product ratios, as shown during the pandemic. But even if this is an easy way out, the pandemic also showed how sensitive and hostile populations are to inflation, and how that can further undermine trust. Nor can this happen without complicit central banks.

Debt management? Default? Governments are forever discussing debt management savings. The US Treasury emphasises ‘regular and predictable’ issuance. But voices often argue that the Treasury should play the yield curve: short-term issuance should be increased given limited rollover risk; others advocate more (less) short-term debt issuance when long-term rates are high (low).

Stephen Miran, chair of the US Council of Economic Advisers, proposed a Mar-a-Lago Accord that called for terming out some foreign-held US debt into 100-year zero coupon bonds or imposing user fees. The proposal flew in the face of US capital market openness. It was akin to a US default, something emerging markets understand and would cause America’s first Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton to tremble in his grave.

In the face of slow growth and mounting fiscal pressures, our political classes avoid responsibility, seeking to do nothing, deceiving the public, arguing a saviour is on the horizon or burying heads in the sand. Citizens resist seeing their benefits shrunk. Reality cannot be escaped forever and the day of reckoning will come. Aggrieved populations increasingly feeling the pinch will turn to despair and populism. However it plays out, it won’t be pretty.

The fiscal chickens will come home to roost.

Mark Sobel is US Chair of OMFIF.

Join OMFIF on 16 October to examine the outlook for US fiscal policy.

Interested in this topic? Subscribe to OMFIF’s newsletter for more.