Since the power crunch in September 2021, the Chinese government’s stance on coal appears to have changed, emphasising energy security as the top priority and recognising that coal is still a key energy source that has to be replaced by renewables gradually. Why is it so difficult for China to accelerate its energy transition away from coal?

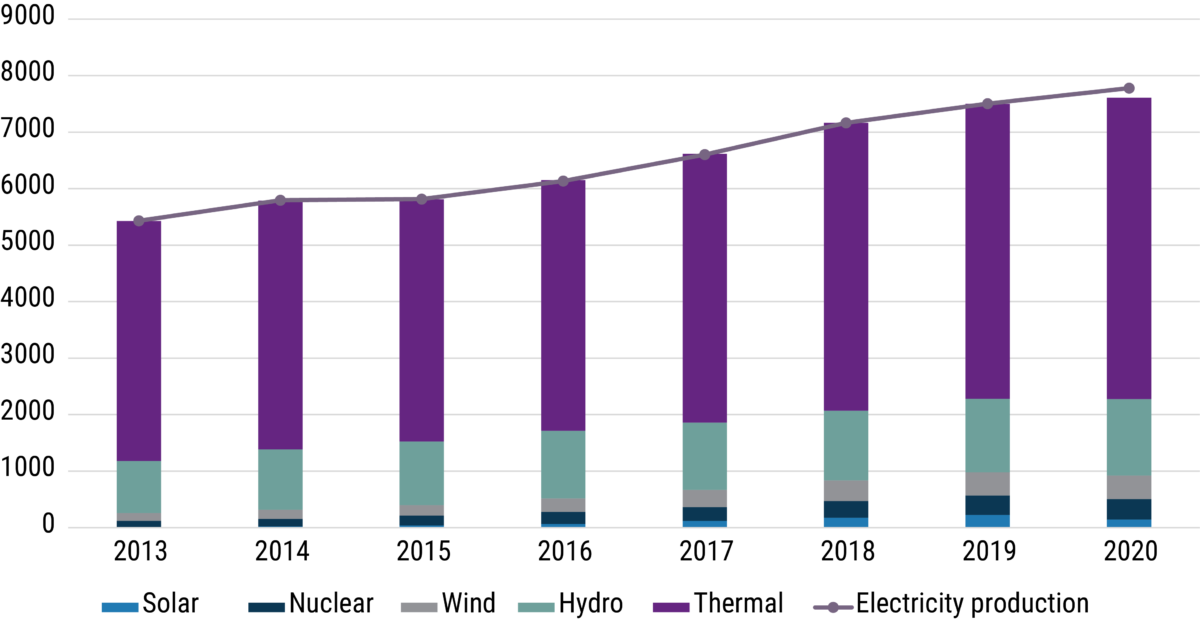

China is now leading the world in renewable development. In 2020, China’s cumulative installed wind and solar capacity took up a global share of 38.5% and 35.9%, respectively. The share of coal-fired power capacity in China’s total power generation mix dropped to below 50% for the first time. However, in the same year, non-fossil fuel energy sources (including hydro and nuclear) provided only 29% of China’s electricity generation, with wind and solar accounting for 7.2%.

Figure 1: China finding it hard to transition to renewables

China’s electricity generation by source from 2013-20, kWh bn

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

China’s economic growth is strong, which brings rising energy consumption. China not only has to replace its existing coal supply with renewables, but also meet the additional energy demand. That means to ensure its energy supply security, coal power can only be replaced by renewables when growth in non-fossil energy power generation is large enough to meet the incremental increases in electricity demand. To achieve its climate goals, the country is planning to increase the share of non-fossil energy sources in its total energy consumption to 25% by 2030 and over 80% by 2060, up from 12% in 2020.

Integrating increasing levels of renewable energy sources into the grid remains a major challenge for all countries, not just China. The power system needs to balance real-time mismatches between electricity demand and supply to ensure grid stability. However, the intermittency of renewables means they cannot be easily ramped up or down on short notice, according to fluctuations in electricity demand.

To enable high penetration of renewables in the grid, countries could significantly expand grid-scale energy storage capacity so that excess electricity can be stored for use at times of high demand. Market mechanisms are critical to the development of commercial energy storage projects, allowing them to develop feasible business models.

However, in China, electricity dispatch is primarily determined by the government’s annual generation plans rather than market-based economic dispatch. Electricity prices do not reflect the scarcity of electricity supply at different times of day and therefore cannot reflect the true cost of system balancing actions. When electricity supplies are tight, regulation measures such as power rationing are often used rather than market-based measures to encourage the development of flexible resources such as energy storage.

Renewables are now cheaper than fossil fuels for electricity generation in many parts of the world. So why does China still favour coal-fired power generation? The management of the power grid is a major barrier as the running of China’s current grid system means that there is a limit to the share of renewables that can be absorbed by the grid. There are various options for improving the flexibility of the power grid, rather than relying on more fossil-fuelled capacity to manage the intermittency of renewables. Power market reform is key to unlocking the flexibility potential of these measures.

Currently in China, the costs for integrating renewables into the grid are mostly borne by power enterprises, squeezing their profit margins and incentives to bring more renewables into the grid. As the proportion of renewable energy sources continues to grow, China should take more measures to improve its ancillary service market, creating proper incentives to encourage a positive interplay between variable renewable generation and the grid.

Chunping Xie is Policy Fellow at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment, London School of Economics.