Earlier this month, Yi Gang, governor of the People’s Bank of China, called for a new general issue of the International Monetary Fund’s special drawing right to mitigate the impact of the Covid-19 crisis.

Under central bank accounting, the SDR counts as a reserve asset which can be redeemed at any other central bank for hard currency. Such an idea had already been mentioned in certain quarters, but the PBoC is the first major central bank to openly call for such a step. The last general issue was in 2009 in response to the 2008 financial crisis – global reserves fell by around $360bn between August 2008 and March 2009, when they were close $7tn. They are now $12tn.

These proposals are admirable, but a general issue is unlikely to happen in the near future. Despite the severe market risk aversion seen in the second quarter, capital flight from emerging markets did not result in severe reserve depletion.

Between March and May, global reserves fell by around $250bn but levels had fully recovered by the end of June. The facilities established by the Federal Reserve in March allowed central banks to obtain dollars without actively running down reserve books.

A general issue would certainly augment existing resources for all IMF members, as Governor Yi and others have stressed. But the biggest beneficiaries need to be small economies with limited to no market footprint and no access to liquidity facilities with major central banks. A designated allocation for such countries would be difficult for the IMF to engineer, as these countries are expected to use the IMF’s existing facilities – with the attached conditionality.

China may have an additional interest in pushing for a general issue, as it is a shortcut to a significant de jure nominal increase in the global level of renminbi reserves.

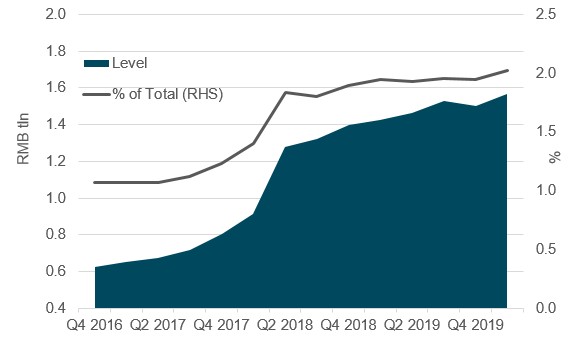

Since the Chinese currency was included in the SDR basket after the 2015 review, the IMF has been tracking renminbi holdings in allocated (reported) reserves. Absolute holdings (figure below) and the currency’s share in total reserves doubled between 2016-18, but progress has since stalled.

Renminbi reserves, total and share

Source: BIS, Bloomberg, BNY Mellon

For the renminbi, a one-off global SDR boost may look good on paper but it is a pure ‘accounting’ gain. The Fed’s extraordinary actions in March to enhance dollar liquidity were necessary because most international cross-border financial claims are denominated in dollars – including for Chinese banks.

For argument’s sake, let’s assume that on an ultimate risk basis, global reserves holdings for a country’s currency should better reflect the level of cross-border bank claims held by the country. Even then, the renminbi actually does not deserve a higher share relative to five years ago.

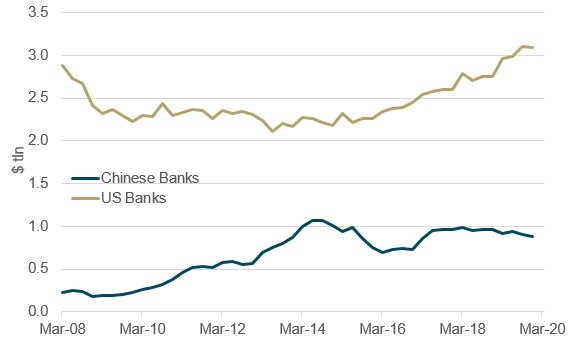

As the figure below shows, as of end-2019 total cross-border bank claims for Chinese banks stood at $885bn, almost unchanged from five years prior and down 17% from the 2015 high. In contrast, during the same period US banks’ international claims have increased by more than 42% to over $3tn.

Total foreign claims

Source: BIS, Bloomberg, BNY Mellon

While Chinese banks and corporates did have ambitions to increase international claims, either directly or to facilitate outbound foreign direct investment, the capital outflow pressures between 2015-19 meant the risks to domestic financial conditions outweighed any potential benefits.

Out of necessity to limit currency instability, Chinese banks deleveraged overseas (as much as onshore). If cross-border liabilities to China did not grow, then central banks had no need to hold more renminbi on reserve. The swap lines between the PBoC and other central banks were barely tapped.

Export growth was unable to make up for a fall in financial claims. Despite a brief recovery in 2017-18, Chinese export growth has been moribund. In dollar terms, 2019 total exports contracted by 6%, and were only around 6% higher than 2013’s total exports. As global commerce declines sharply amid the pandemic, there is little scope for trade-driven renminbi liabilities to grow.

If organic growth channels for renminbi demand are lacking, then it doesn’t hurt to try to generate said demand. After an almost unprecedented global demand shock, countries will be counting on an investment drive to recovery, especially in infrastructure.

Chinese provinces have proposed upwards of Rmb50tn (equivalent to more than 50% of GDP) over the next five years for ‘new infrastructure’ investment. However, there are likely to be concurrent plans to engage in similar investment overseas through bilateral agreements or the Belt and Road initiative. Despite the clamour over ‘new infrastructure’, China has plenty of excess capacity in ‘old infrastructure’ which needs to be exported.

It is clear Beijing sees a potential second wind for renminbi internationalisation, highly contingent on China helping finance the recovery in places willing to accept. Meanwhile, the IMF offers multiple routes for an accounting-driven reserve boost for the renminbi.

The PBoC’s hopes for an immediate one-off special SDR issue might be a long-shot, but the next quinquennial review of the SDR basket is due to be completed by the end of the year (but may be subject to Covid-related delays).

Beijing will probably demand a lift in the renminbi’s share – another step on the long path to establishing a currency bloc and chip away at the dollar’s dominant status.

Geoffrey Yu is Senior Europe, Middle East and Africa Market Strategist at BNY Mellon.