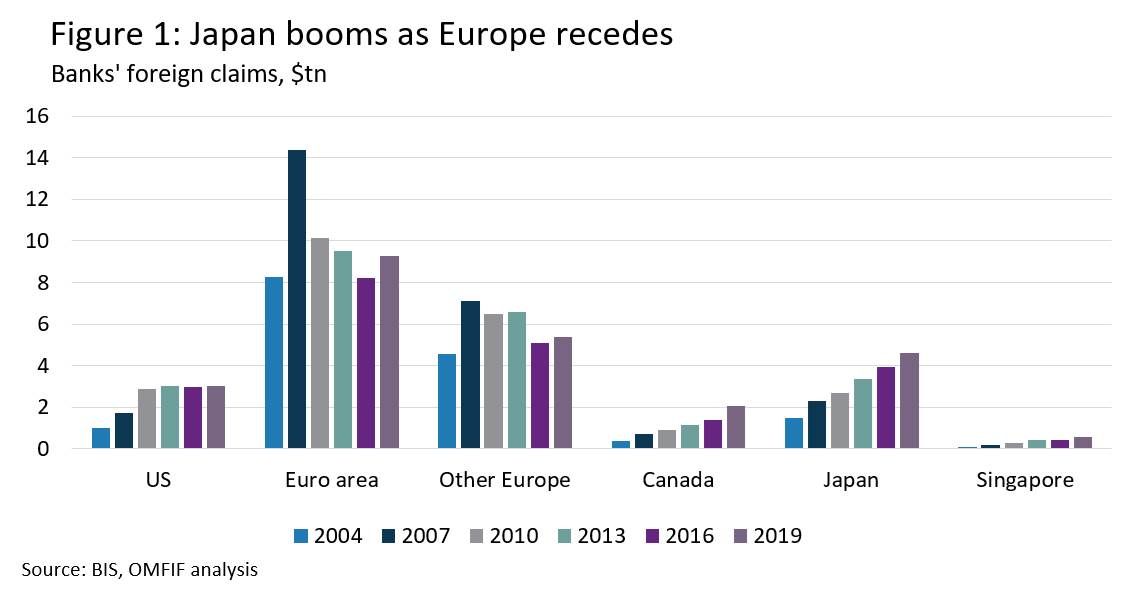

The 2008 financial crisis caused banks across Europe to reel in their cross-border business. This business has not improved much since, only rising a small amount between 2016-19, as Figure 1 shows. US banks have fared better. Figure 1 shows end-year data, which masks a stronger 2019 average.

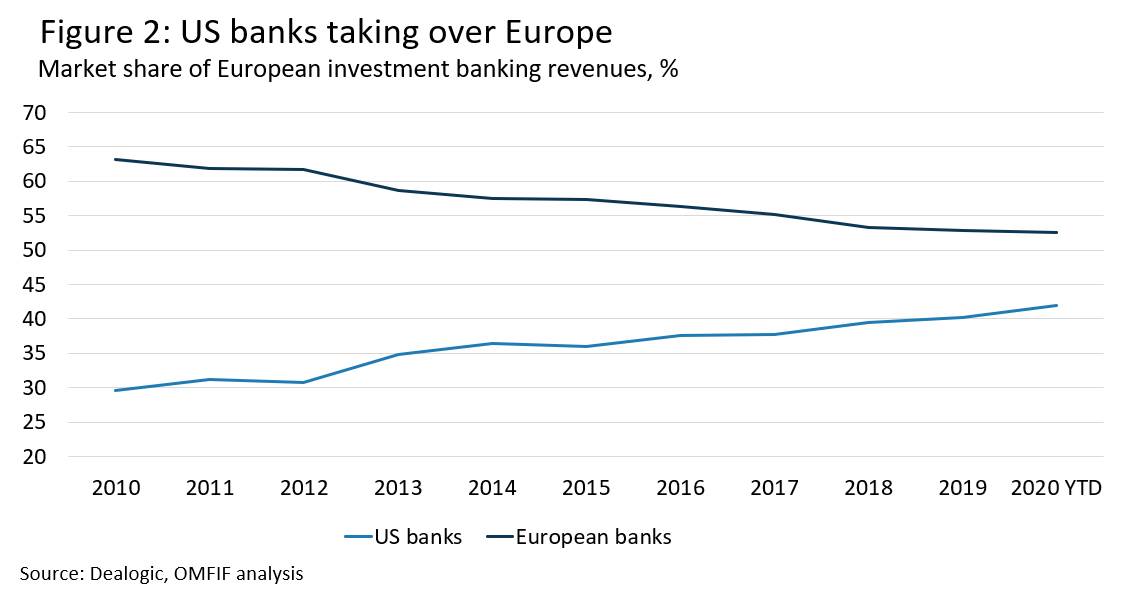

US banks have moved in where European banks have moved out, gaining market share across Europe. US banking groups have secured 42% of investment banking revenues earned in Europe so far this year, according to data from Dealogic. Their market share has risen over the last decade at the expense of European rivals, as Figure 2 shows.

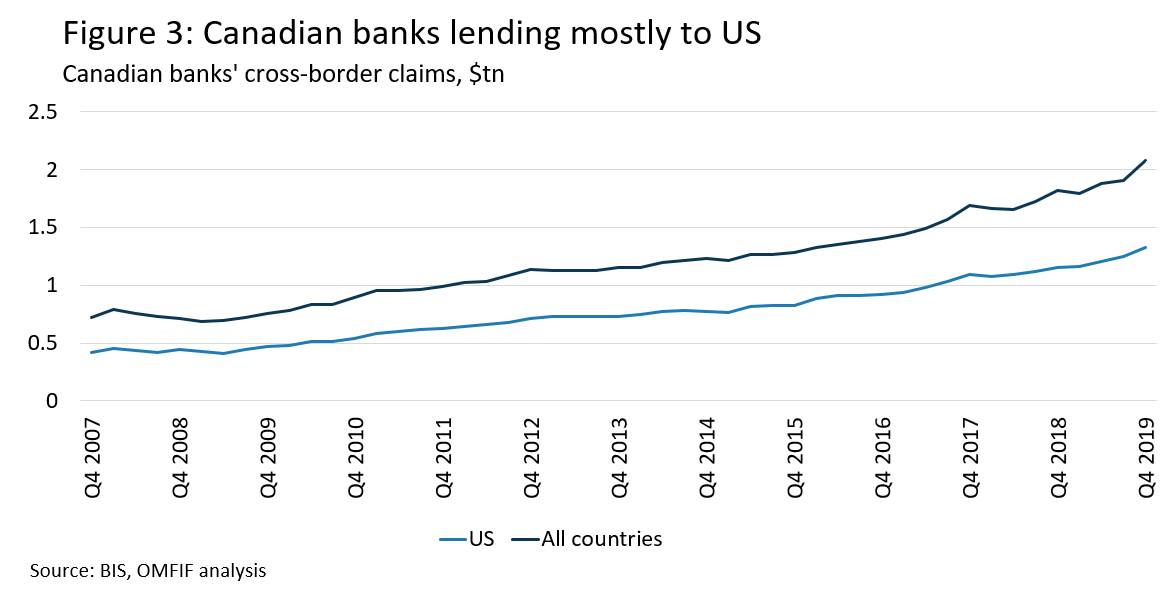

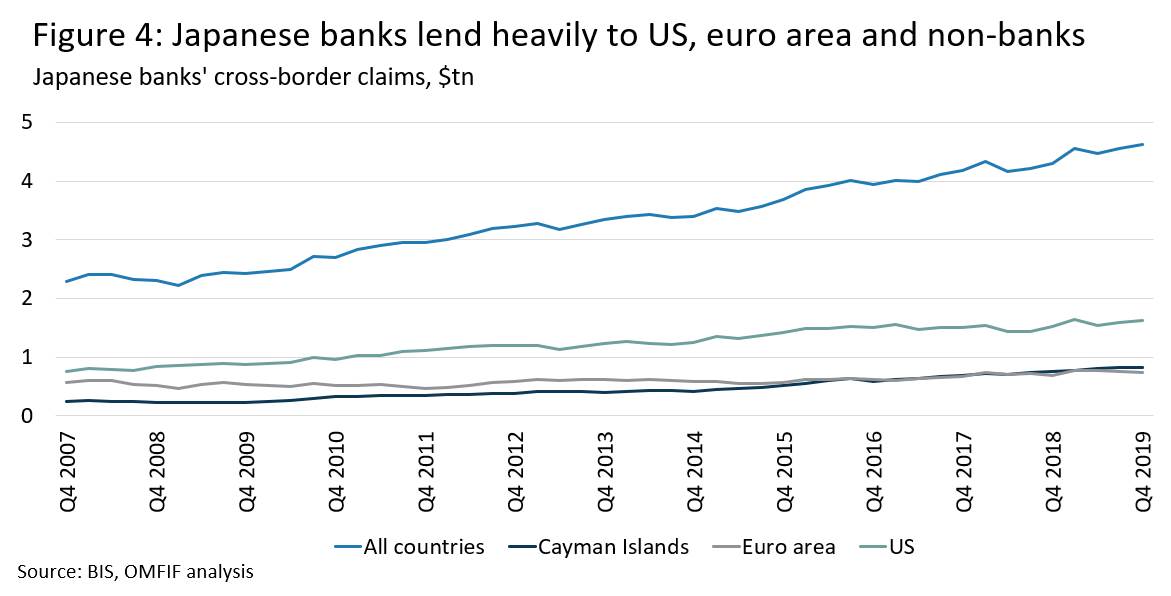

While US banks expanded into Europe, Canadian and Japanese banks expanded into the US as they rapidly bolstered their cross-border activities. Since 2004, Canadian banks’ foreign claims have increased more than five-fold, and Japanese banks’ more than three-fold. Most of this investment has gone into US assets, as seen in Figures 3 and 4, with banks tempted by higher net interest margins than in their home markets.

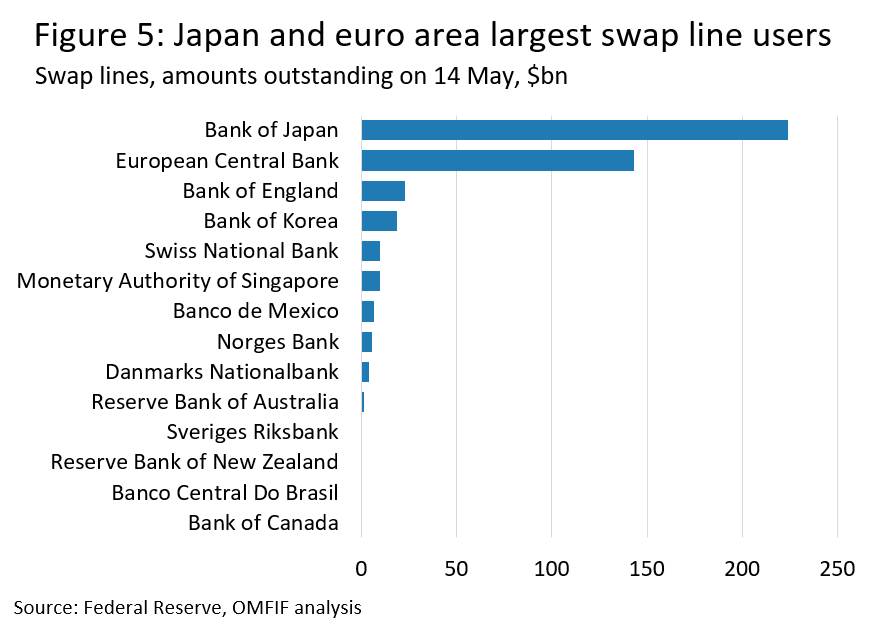

Most of this cross-border lending will be in dollars, and it may be expected that Japan and Canada would make greater use of the Federal Reserve’s dollar swap lines. But as Figure 5 shows, Japan has used it heavily while Canada has yet to use it at all.

Most of this cross-border lending will be in dollars, and it may be expected that Japan and Canada would make greater use of the Federal Reserve’s dollar swap lines. But as Figure 5 shows, Japan has used it heavily while Canada has yet to use it at all.

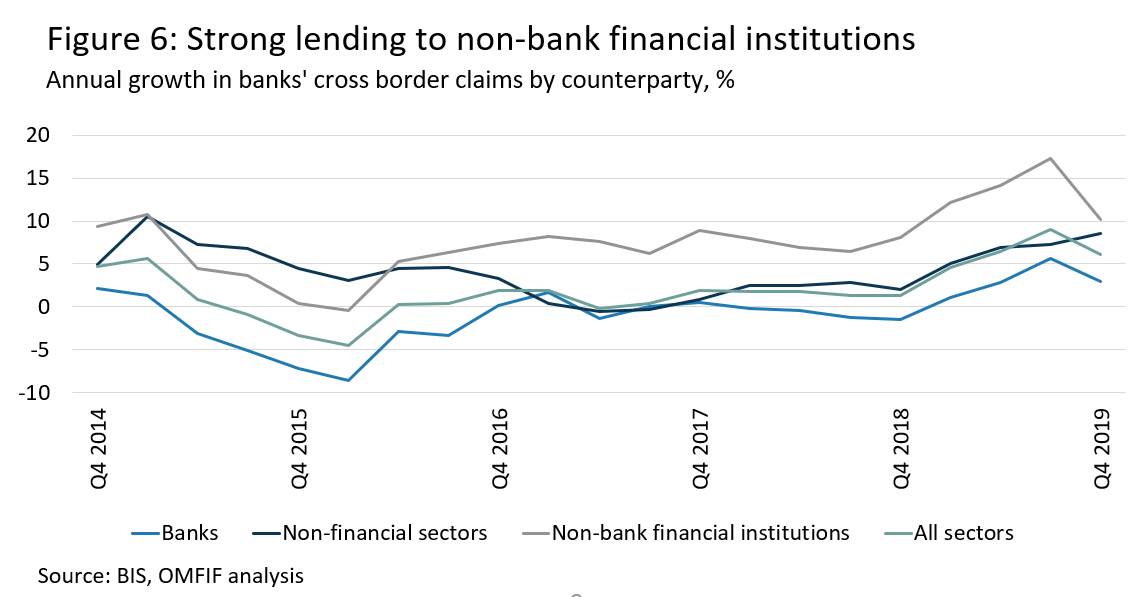

Aside from lending to the US, Japanese banks have been lending heavily to institutions in the Cayman Islands. As a tax haven, the Cayman Islands is an attractive location for non-bank financial intermediaries that channel money globally. This lending reflects the broader trend of non-banks conducting banking business and playing a more significant role in wholesale funding markets. Figure 6 shows that lending to non-bank financial institutions has been the fastest-growing component of cross-border lending since 2015.

This is a policy choice. Policy-makers are keen for more financial intermediation to go through funds rather than banks. Sometimes this makes sense. For example, a pension fund has much more stable funding – there has never been a run on a pension fund in the way there has been a run on banks. But not all funds are pension funds; some will no doubt also have short-term liabilities and long-term assets. We cannot know for sure, as unlike with banks, there is no comprehensive data on non-bank financial intermediation. Funds operating in wholesale markets tend to be smaller and more numerous than banks and based in offshore financial centres; they are a blind spot of the global financial system.

China is also worth a mention. Its cross-border banking activities are small compared to other major financial centres, but as the Economist discussed in a recent special report, China’s foreign lending activities, including those related to the Belt and Road initiative, are driving an increase in the country’s cross-border claims, especially in emerging markets and Africa.

These financial linkages could spill over into the world of geopolitics, affecting the relationship between the US and Europe, Canada and Japan. They also highlight where risks lie should the Covid-19 crisis extend more significantly into the financial realm, with Japanese banks and some sections of non-bank finance looking precarious.

Chris Papadopoullos is Economist at OMFIF.