The renminbi exchange rate is woefully undervalued – an impediment to overhauling China’s distorted growth model and a major contributor to global trade tensions. While it is no secret that the currency is tightly managed, the time has come for Chinese authorities to allow the renminbi to appreciate substantially.

Renminbi developments

For much of 2024, the renminbi faced large downward pressures despite a massive current account surplus. This disconnect reflected persistent capital outflows partly mirroring China’s strong economic headwinds, such as continuing housing woes, deflation, weak domestic demand and a lack of confidence.

The authorities manage the renminbi with a close eye on the dollar. As the dollar faced generalised downward pressure in the first half of 2025, Chinese authorities resisted renminbi depreciation. They understandably feared that a falling renminbi could unleash global financial market turmoil, including a self-perpetuating fall in the currency, reminiscent of 2015-16.

In the last two months, however, conditions have improved. The spot renminbi and the official fixing rate are now broadly aligned whereas a few months ago the spot rate was trading towards the depreciated edge of the +/-2% band.

Market sentiment has improved, reflected in strong Chinese equity gains. Rising expectations that the Federal Reserve will begin cutting rates in coming months portend some narrowing in the large yield differential favouring US assets. In the meantime, progress in US/China trade discussions, alongside ‘deals’ between the US, Europe and Japan, are dispelling some of the market’s worst protectionist fears and providing a modicum of clarity.

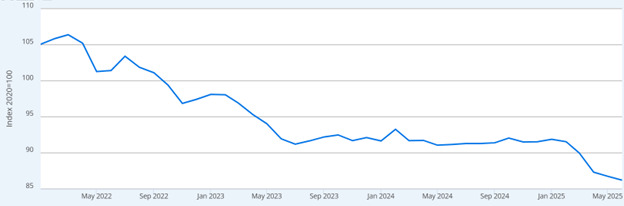

China’s growth forecasts for this year are also being marked up, with the International Monetary Fund recently upgrading its 2025 forecast from 4.0 to 4.8%. But broad stability against the dollar amid the latter’s depreciation in the first half of 2025 meant the renminbi gained even more competitiveness against others, just as it had after the Covid-19 pandemic. The upshot is that the real renminbi has fallen nearly 20% since early 2022.

Figure 1. Falling renminbi since start of 2022

Real broad effective exchange rate for China

Source: Bank for International Settlements via FRED

The renminbi is massively undervalued. The IMF estimated the undervaluation was 8.5% in 2024. But this was based on an estimated current account surplus of 2.3% of gross domestic product, whereas given a trade surplus on the order of 5% of GDP and assuming China’s income was broadly in balance, not deficit, one could have arrived at a current account surplus on the order of 4%. That would imply a far greater degree of undervaluation. Many of these trade and services trends continue unabated in 2025. Robin Brooks of the Brookings Institution estimated that the renminbi’s undervaluation is above 20%.

A weak renminbi is an integral part of China’s growth model

Chinese and foreign economists have long called for overhauling China’s growth model. That model significantly relies on high savings and channelling them via state-owned commercial banks into state-owned enterprises. In turn, the enterprises manufacture goods far more than domestic absorptive capacity, which then find outlets in international markets and large Chinese trade surpluses. These trends are reinforced by authorities setting unsustainably high growth targets, as Michael Pettis has well pointed out.

Renminbi weakness reinforces China’s export reliance, while dampening imports. As a result, external demand has been a persistent growth driver, and especially so now. China accounts for 30% of global manufacturing and its manufacturing surplus exceeds 10% of its GDP.

It is highly understandable that countries across the globe fear Chinese overcapacity spilling into their markets. Europe has even more reason to do so given President Donald Trump’s efforts to curtail Chinese access to America.

Those calling for reform have long argued for China using fiscal income transfers to knit a stronger safety net, strengthening consumption while dampening saving and boosting services. But authorities, increasingly recognising these arguments, have not followed suit with conviction, instead treading cautiously, notwithstanding near deflation. They are worried about excess fiscal indebtedness and the social fallout from shifting production away from manufacturing. Using aggressive monetary policy accommodation would run the risk of triggering capital outflow and large renminbi depreciation.

Let the renminbi rise

A stronger renminbi on a real trade-weighted basis and against the dollar is part and parcel of overhauling China’s growth model. It must complement a reorientation of fiscal policy and move away from state-led investment growth, along with authorities accepting that China’s sustainable growth rate is much lower than their excessively high growth targets. The authorities also need to accept that massive surpluses – when China is the world’s second largest economy accounting for over 15% of the world’s GDP – will generate huge unacceptable spillovers for other countries and the global economy. A weak renminbi also further heightens competitiveness since China’s inflation is lower than abroad.

A strong renminbi would help lift domestic demand, boost real incomes, convey a strong signal of official support for the Chinese economy to produce non-tradable goods and services for the domestic market and help fight ‘involution’. China will still remain highly competitive. Chinese authorities might fear that a stronger renminbi would reinforce deflationary pressures. However, those forces can be offset via fiscal transfers, which again is precisely what is needed through strong action, not lukewarm measures or rhetoric.

China has a tradition of limiting exchange rate movement when global conditions are tumultuous, such as during the 1997-98 Asian and 2008-09 financial crises. But when conditions steadied after the 2008-09 financial crisis, China permitted significant appreciation. Notwithstanding China’s current challenges, that time has come again.

Mark Sobel is US Chair at OMFIF.

Interested in this topic? Subscribe to OMFIF’s newsletter for more.