That the US will inevitably devalue or renege on its sovereign debt, probably through inflation and money-printing, found easy consensus at a recent private dinner for family offices and sovereign funds attended by OMFIF.

A furious and intractable row broke out, however, about whether gold or bitcoin was the better alternative to the dollar, while the renminbi and the euro went unmentioned. If a reserve manager were also present it would perhaps have swung the argument.

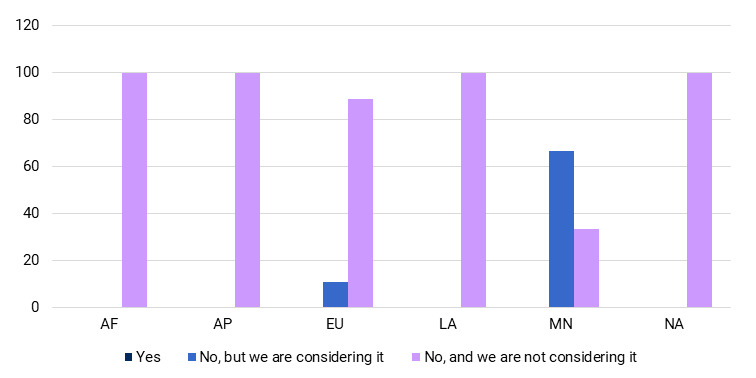

OMFIF’s Global Public Investor 2025 found that not a single central bank surveyed holds any digital assets, and 93% have no intention of doing so. Of the institutions in question, representing $5tn of global reserves, there were outliers in the Middle East plus a lone voice in Europe (Figure 1). The pronounced conservativism extended beyond distributed-ledger technology assets to the technology itself: 82% of respondents neither use it nor intend to in future, even though some of their central bank digital currency teams are getting ready to do so.

Figure 1. No central banks hold digital assets

Do you invest in digital assets?

Source: Global Public Investor 2025 survey

What is holding the vast majority of reserve managers back from the crypto party, at a time when the same survey found 58% looking for diversification?

Even though they resemble reserve-like money more than they resemble securities, the main reason not to hold stablecoins is very simple. Regulators – including central banks – are mostly intent on preventing them from paying a yield (which is also why their operators are incredibly profitable). As Larry Hathaway, global investment strategist at Franklin Templeton, explained at the launch of the GPI report, there wouldn’t be many takers for this kind of ‘negative carry’, and reserve managers might as well directly hold the kind of government money market instruments that sit in stablecoins’ collateral pools.

Daniela Klingebiel, who helped manage the Reserve Advisory and Management Partnership for the World Bank, added a host of other factors militating against stablecoins as a reserve asset, rather than as a means of payment. These include legal and counterparty risk, custodial complexity, regulatory ambiguity, technical risk, credit risk (of the coin issuer) and the risk of de-pegging, which for example both USDC and USDT have done, and happens occasionally to money market funds, which somewhat resemble stablecoins.

What about digital assets that more resemble securities or commodities, such as bitcoin? Some observers refer to it as the ‘new gold’, primarily on the basis of its programmatic scarcity. Similar ecosystem obstacles exist to those for stablecoins, Klingebeil explained, in addition to the nature of the asset itself, which is volatile, illiquid and harder to trade compared to typical reserve assets. Nor is bitcoin (yet, at least) used for cross-border trade and capital flows, both of which also significantly determine a national reserves managers’ allocation strategy.

What of the 7% of reserve managers at least keeping an eye out? At the GPI launch, Jan Kubíček, board member, Czech National Bank, said ‘we can pretend there is no such thing as bitcoin or gain some hands-on experience with it’, adding that this does not immediately equate, say, to 2% of reserves. The ecosystem differences to other types of assets, including auditing and accounting treatment, posed major challenges, ‘but still we are open to experimenting with it’.

The CNB has also explored the potential benefits of (non-)correlation, but ‘not discovered any miraculous stabilising force’ through a portfolio holding of bitcoin, though all these factors may significantly change ‘as it becomes more financialised’.

Public pension and sovereign funds, whose allocation objectives are more return-focused and less complex and systemic than central banks, are more adventurous. In the same survey, 7% of those respondents already hold digital assets, and a further 20% intend to.

Figure 2. Low appetite for bitcoin reserve

Do you foresee your central bank building strategic bitcoin reserves?

Source: Global Public Investor 2025 survey

Facts on the ground march on. President Donald Trump has announced that the US would set up a strategic bitcoin reserve. The Genius Act, presaging the mainstream adoption of stablecoins in the US, has been passed by the Senate and awaits approval in the House of Representatives. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac may soon treat cryptoassets as legitimate collateral for housing finance.

The future path of stablecoins remains intriguing. They lack the value creation of programmatic scarcity and, for the most part, have no yield. They are not backed, for now, by central bank reserves, merely government debt and fiat cash. They have de-pegged in the past. OMFIF has heard that hedge funds are waiting to test them in a market dislocation. So why bother?

Stablecoins are saving counterparties material sums on payments. At an off-record event convened by a global universal bank and some of its key wholesale customers as well as OMFIF, a major consulting firm said that it is already using stablecoins for internal cross-border payments. The bank in question, a major transactions services player for whom this could be an existential headache, could afford to relax a little, though.

A leading multilateral development bank in attendance said that it did not wish to take on the theoretical risks of using stablecoins even for a short time, and would prefer to use the service in development by the bank, which uses stablecoins in the background to remit more quickly and cheaply.

If, in the end, the stablecoin and DLT boom makes the regulated financial sector faster and cheaper, it will have ended up at a version of the Regulated Liability Network, thanks to the advancing threat of the opposite, which will leave the financial system broadly as it is.

John Orchard is Chairman of OMFIF’s Digital Monetary Institute.

Download OMFIF’s Global Public Investor 2025. Watch the launch event on demand.