Psychodramas involving UK prime ministers and chancellors are not new. The most recent episode in which Prime Minister Keir Starmer abandoned £5bn cuts in benefits sought by Chancellor Rachel Reeves is particularly serious because of the potentially damaging consequences for the government bond market. From now on tax and spending decisions will be largely dictated by judgements on what the markets will accept.

The last-minute abandonment of the proposed benefit cuts will increase suspicion about the degree of commitment to any difficult policy decisions in the future. The market background is already difficult: the yield on UK government debt has risen since the general election and is higher than for G7 and European peers (Figure 1).

Figure 1. UK yield curve has risen since last year’s election

Source: LSEG and Bank of England

The credibility of UK fiscal policy will be the key to market confidence. While there is a very strong case for curbing the future growth in the benefit bill there is now no chance of progress in the immediate future. Any attempt to loosen the fiscal rules would involve colossal risks with the markets.

Since most of the recent pressures to raise public spending or to avoid cuts concern current expenditure it will be even more important to stick to – or improve on – the target to cease borrowing for current spending on which there has been no recent progress.

Managing the market for UK government debt

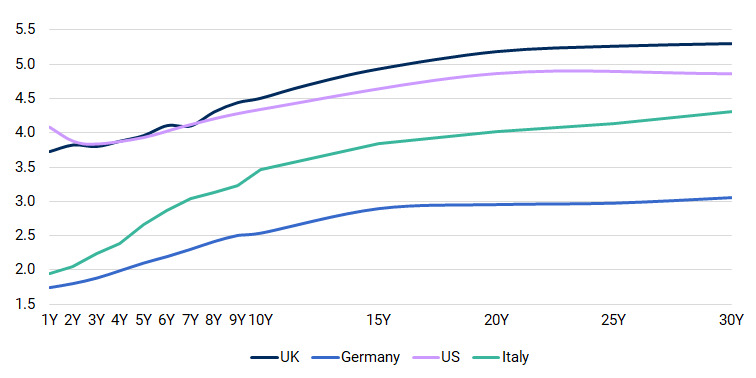

The government will need to treat the gilt market with particular care and to avoid at all costs a further sharp rise in yields. Gilt yields have risen for all but the shortest maturities since the 2024 general election. They are higher even than US yields, notwithstanding President Donald Trump’s fiscal profligacy and the generally chaotic nature of US decision-making, notably on trade policy. France and Italy have higher government debt burdens than the UK, yet the yields on their government debt are significantly lower (Figure 2).

Figure 2. UK has higher bond yields than Germany, France and Italy

Source: LSEG

Both the rise in the yield on UK debt during the past year and the fact that yields are higher than for peer economies are evidence of unease about UK government policy in international bond markets. To reduce market unease significantly it will be necessary to reduce borrowing substantially during the rest of this parliament through a combination of cuts in spending and tax increases. This is not likely to happen.

The hope is that markets will be satisfied – to the extent of not forcing up gilt yields further – with compliance with the existing fiscal rules by the end of this parliament. In the absence of spending cuts, this is likely to involve a substantial increase in tax receipts, though the exact amount depends on how the OBR (and other forecasters) see economic prospects at the time of the autumn budget.

In the meantime, the government should make a public commitment at the highest levels that it will not countenance more borrowing than was planned as a way out of its fiscal difficulties. Finally, the Bank of England should stop adding to market pressures and discontinue its gilt sales through its quantitative tightening programme.

Fiscal policy options

Caught between the opposition of its MPs to cuts in public spending and the likely problems in bond markets that any increase in planned borrowing would cause, the government will be forced to increase taxes, possibly by tens of billions of pounds. The temptation will be to look for extra revenue from the wealthy in areas like capital gains tax, pensions or company tax.

Changes in the tax regime in such areas should be part of a considered process of long-term tax reform and not the result of a hurried hunt for revenue. The side effects of such changes can be difficult to predict – defensive behaviour to reduce tax liability is highly likely and could materially reduce expected yields.

The least damaging course would be to raise extra revenue with a broad-based increase in income tax or VAT. While this would break a manifesto commitment, it could be argued that the circumstances in the world and UK economies are very different from those expected a year ago and that such a tax increase is the least bad option.

Public presentation of macroeconomic policy

The objective should be not only to stabilise fiscal policy but to bring some order into its public presentation. The government’s stated aim was to have one main fiscal event each year in the autumn. The record since the general election has been quite different, with numerous significant announcements for fiscal policy beginning with the original winter fuel payment curtailment and most recently with the cancellation of the benefit cuts.

It would be more realistic for the time being to revert to just two fiscal events – in the autumn and spring – each of which should be accompanied by an OBR assessment. The firm intention should be for all announcements of significance for fiscal policy to be made in one of the twice-yearly events and to be fully assessed by the OBR at the time of announcement.

Peter Sedgwick was a senior UK Treasury official, Vice President of the European Investment Bank from 2000-06, Chair of 3i Infrastructure PLC from 2007-15 and Chair of the Guernsey Financial Stability Committee 2016-19.

Over the past three years, OMFIF has collaborated with EY to explore how to improve public finance management. This year’s project examines how governments can more effectively allocate public funds to support better fiscal, economic and societal outcomes. Find out more here.

Image source: House of Commons

Interested in this topic? Subscribe to OMFIF’s newsletter for more.