Scott Bessent’s Treasury released its first Foreign Exchange Report on 5 June. The report was accompanied by much chest-thumping Trumpian rhetoric about unfair foreign practices. But it also delivered a substantively mainstream assessment, in line with recent reports. That is a good thing and the Treasury got it largely right, despite some failings in connecting the dots between American policies and their global interactions.

The press release and FXR came out swinging with tough rhetoric on ‘destructive trade deficits’ and ‘unfair trade practices’. But in substance, this FXR is little different from Secretary Janet Yellen’s. The FXR found no ‘manipulators’ – how could it when many countries have been resisting depreciation? The monitoring list is only slightly changed. The market yawned.

The report is filled with strong technical analysis, which is testimony to the Treasury’s outstanding international affairs team. Yet the FXR could have dug deeper. That is clearest with respect to the opening discussion of the US economy, exchange rates and global imbalances. Those sections provide comprehensive data and descriptions.

Bessent’s Institute for International Finance speech rightly emphasised that GIs were a major international economic problem, warranting renewed focus. He fairly suggested the International Monetary Fund’s GIs work habitually suffers from timidity. The FXR justifiably focuses on China’s large surpluses as a chief culprit.

But the US is the largest counterpart to the world’s surpluses. America’s contribution to GIs is massive and it’s largely a ‘Made in the USA’ story, a point the FXR fails to draw out. That is where the FXR fell short in connecting the dots.

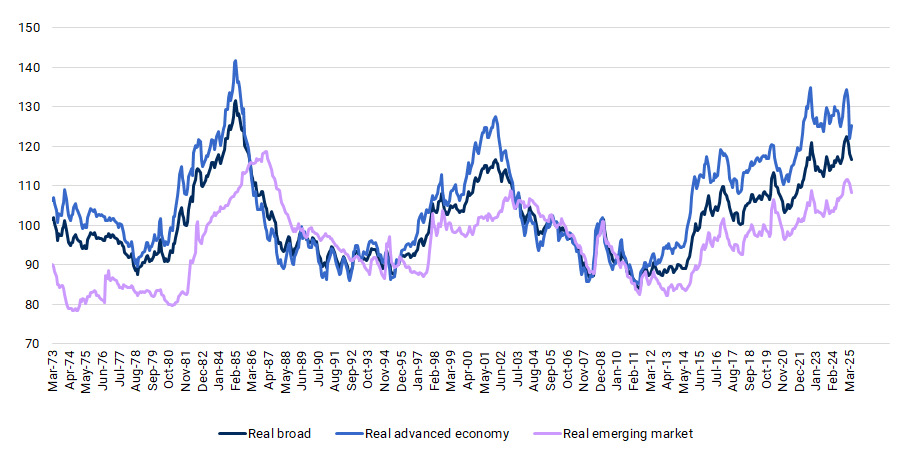

The dollar rose sharply under the Joe Biden administration. Despite recent dollar depreciation in response to weaker market confidence over President Donald Trump’s economic policy management, the real dollar remains very strong (Figure 1). That reflects both US monetary and fiscal policy developments.

Figure 1. Real dollar remains very strong

Real trade-weighted dollar

Source: Federal Reserve and author’s adjustments

America’s current account deficit reflects its dearth of savings. The US could act to raise household and governmental saving. The latter would require reducing massive fiscal deficits, which could also help lower the dollar. The ‘Big Beautiful Bill’ heads in the wrong direction. If America wants a lower dollar, it would be far preferable to achieve that through the pursuit of sound policies rather than undermining global trust in America’s economic leadership.

More forceful analysis of China’s contribution is also warranted. The FXR includes a robust discussion of Chinese external developments, noting efforts to resist depreciation against the dollar in view of capital account pressures. The Treasury rightly hammers away at the opacity of Chinese exchange rate practices.

But the Treasury could focus even more heavily on how China’s broken growth model contributes to GIs, a topic intertwined with external policies. Many analysts argue China sets unsustainable high growth targets, suppresses consumption and uses excess savings to fund investment via state-owned banks along with industrial policy to prop up state-owned enterprises. Further, China produces excess capacity unable to be absorbed domestically and the surplus is shipped abroad. This is happening amid a highly undervalued exchange rate (Figure 2).

The Treasury mentions these points. But future FXRs might more comprehensively underscore the Treasury’s views on this nexus, including in a separate box. Also, the Treasury could posit whether it believes China has considerable fiscal space.

Figure 2. China’s exchange rate is highly undervalued

Source: Bank for International Settlements via FRED

The FXR also surprisingly seems to directly criticise the Bank of Japan for not raising interest rates more quickly and thus providing insufficient support for the yen. While analysts may debate whether the BoJ should be more proactive in lifting rates, one should not discount that there are also key domestic factors weighing on BoJ caution, which need to be balanced against rate hike arguments. It is rare, if not indecorous, for major advanced economy financial authorities to overtly criticise another’s monetary policies, rather than in more couched terms.

On Vietnam, the FXR rightly underscores that Chinese transshipments are unacceptable. But the Treasury knows that Southeast Asian centres offer favourable foreign direct investment conditions. Blanket reshoring to America won’t happen. The US needs to decide whether firms leaving China and setting up in Vietnam is on balance a plus or minus in lessening China’s global footprint.

Switzerland finds itself again on the monitoring list. The Treasury does a good job in describing Switzerland’s economy. But it could again better connect dots, more explicitly highlighting that Swiss monetary policy faces unique challenges because of the interplay between a safe-haven currency, low inflation, small government debt and a highly open economy.

The report rightly focuses favourably on Germany’s fiscal U-turn and the positive impact this may have in reducing longstanding excessive current account surpluses.

The next FXR should go beyond description and bear down on the Taiwan dollar’s recent appreciation, a currency long highly and persistently undervalued including due to governmental actions.

All in all, beyond the opening theatrical verbiage, the Treasury offers a solid report that basically gets much right.

Mark Sobel is US Chair of OMFIF.

Join OMFIF on 24 June for the launch of Global Public Investor 2025.

Interested in this topic? Subscribe to OMFIF’s newsletter for more.